narrative, lyric, drama

Narrative, Lyric, and Drama are the three general literary forms into which writing, especially poetry, has traditionally been grouped. A narrative tells a story or a tale; drama is presented on a stage, where actors embody characters; lyric has been loosely defined as any short poem other than narrative and drama, where poets express their state of mind.

Narrative

Narrative or story telling developed from ritualistic chanting of myths, and has traditionally been grouped into two poetic categories, epic and ballad. The stories were not memorized as is generally assumed but instead bards improvised oral chants, relying on heavy alliterative and assonantal techniques, which seemed to put both the bard and the audience into a trance (Preminger 542).

An epic is a long non-stanzaic "poem on a great and serious subject, told in an elevated style, and centered on a heroic or quasi-divine figure on whose actions depends the fate of a tribe, a nation, or the human race" (Abrams 51). Typical figures include demi-gods, kings, and military heroes. Even a millennium before Homer, bards were recording an already ancient oral tradition of epic poems in Sumer and Egypt (Preminger 544). More modern epic poems have been recorded in Spain and France, the Ottoman Empire, and as late as the 20th century in the Balkans.

Stylistically similar to epics, the ballads are story poems that could be chanted in groups about common people. When written down, they are typically divided into abcb -rhymed stanzas to emphasize the elements of song. Repetitive frames are also frequent within the poem, and the narrative itself is episodic and abrupt in transitions. Common themes include courage in war and stories of love.

During the Middle Ages, narrative poems transformed into courtly romance stories – Christian stories about heroic knights and the spiritual temptations they face on their journey, such as the Arthurian legends. Many of these stories also reduced to religious allegories, such as the epics of saints' lives.

Drama

Drama in Western civilization has had two parallel beginnings, both related to religious celebration: the first in Ancient Greece and the second in medieval church plays. In his Poetics, Aristotle defines drama as being made up of Plot, Characters, Diction, Thought (or propriety), Spectacle (such as scenery, lights, and special effects), and Melody (musical accompaniment) (632) [see melos, opsis, lexis]. This elaborate definition has since been revised and narrowed down to "a story told in action by actors who impersonate the characters of the story" (Holman 154).

Ancient Greek drama arose from the dithyramb, a song and dance celebration in honor of the wine god Dionysus. In the first staged plays, the dramatists added a non-chorus character that spoke to the chorus; the main plot was the tension that arose from their question and answer dialogue. (Plays in other cultures such as Ancient Egypt, China, and Japan likewise began from celebrations of gods.) Eventually, dramatists added more characters and complicated the plots. The Romans inherited and built upon the Greek dramatic form; together, the Greek tragedies and Roman comedies provided a basic foundation for European drama until as late as the 19th century (once they were rediscovered in the Renaissance).

Drama had a second beginning in the church plays of medieval Europe. Church fathers wrote religious plays as a way of staging Biblical stories during religious holidays. They often built makeshift stages on carts that were used to move around towns between performances. Typical Bible stories included the creation, Noah's ark, the crucifixion, and the apocalypse.

Drama has often been the site of extreme controversy. Inherent in the form seems to be a tradition of experiment and revaluation (Preminger). For example, until the late 1600s, audiences were opposed to seeing women on stage, because they believed it reduced them to the status of showgirls and prostitutes. Even Shakespeare's plays were performed by boys dressed in drag. In the early 1800s, riots frequently erupted over the dramatic form itself. French neoclassicists, who followed the Greek and Roman writing styles, would often quarrel with the new, more poetically rich Romantic style, which emphasized the Spectacle. Similar riots occurred again just before the 20th century over the naturalistic/representational style, where internal character motivation and "fourth wall" acting were becoming more predominant.

Lyric

Lyric is a loosely defined term for a broad category of non-narrative, non-dramatic poetry, which was originally sung or recited with a musical instrument, called a lyre [see voice, sound]. Generally, lyric poets rely on personal experience, close relationships, and description of feelings as their material. The central content of lyric poems is not the story or the interaction between characters; instead it is about the poet's feelings and personal views [see expression]. Examples from this group include Greek odes, Egyptian elegies, Hebrew psalms, English and Italian sonnets, and even the Japanese haiku.

Originally, the lyric began as a song chanted to the praise of gods. But like the epic and ballad, it soon transformed to praise of heroes and loved ones. For example, poets like Ovid, Martial, and Catullus wrote verse epistles to friend and would-be-lovers, and Jewish poets wrote in a highly subjective style in the Hebrew psalms, often addressing God as if a close confidant or even a lover.

Many early European poets, such as Petrarch, Shakespeare, and Sidney, updated the lyric tradition by writing long sonnet sequences in praise of their mistresses. At the same time, religious poets like Herbert and Vaughan used lyrics to describe their relationships to God and Christ.

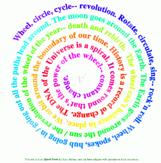

After 1600, lyric poetry developed into three main types: Lyric of Vision, Lyric of Thought, and Lyric of Feeling (Preminger 465). Vision lyrics, or concrete poems, represent structurally what the words convey in concept. George Herbert, for example, made his religious poems look like an angel's wings or a preacher's altar; likewise the famous E. E. Cummings poem "[1(a]" traces a falling leaf across the page. The spiral image on the right is an example of a concrete poem by Sasu Jeffrey. It is a thesaurus-like list of words that mean spiral, including "wheel," "circle," "rotate," "circulate," and "death and rebirth."

Thought poems are informative and didactic, such as allegories and satires. Pope and Dr. Johnson, for instance, used satire to ridicule folly and teach Londoners about what they saw as the fading traditional values of England; and Ben Jonson wrote verse epistles to explain such things as the rules of eating temperate dinner.

Thought poems are informative and didactic, such as allegories and satires. Pope and Dr. Johnson, for instance, used satire to ridicule folly and teach Londoners about what they saw as the fading traditional values of England; and Ben Jonson wrote verse epistles to explain such things as the rules of eating temperate dinner.

Lyrics of Feeling comprise the largest of the three groups; included are sensual, intellectual, and mystical poems (Preminger 469). Mystical poems have often been referred to as the opposite of concrete poems, because instead of presenting images through their structure, they rely solely on their content to paint a new visionary world; Blake is one example. Sensual poems include love and drinking poems by the Greco-Roman poets and early sonneteers, plus poems on the musings of nature by the Romantics. Prototypical intellectual poems can be seen in the German Romantics and French Symbolists, who try to intellectually describe their personal states and feelings.

For a long time, many scholars have been debating about the status of these literary forms. At issue is the value of maintaining these distinctions, especially since they no longer accurately reflect modern poetic and media trends.

It is well known, for example, that narrative prose such as the novel overshadowed poetic story telling as early as the 1800s. More recently, cinema, Hollywood movies, and TV shows have overshadowed even the novel. In fact, modern media have forced all three literary forms to redefine themselves. Elaborate descriptions of landscape have been adopted by photography; introductory chapters that present character background have been transformed into complex motivation for the screen actor; deep lyrical subjectivity is now an off-screen monologue.

Moreover, much of modern art has been stripped of its content, so that the bare minimum of lyric and drama remain: sound and theatricality. According to Modernist scholars, poetry should be about sound: "to give full play to its true affective power it is necessary to free words from logic. . . . Poetry subsists no longer in the relations between words and meanings, but in the relations between words as personalities composed of sound" (Greenberg 33). It is perhaps no coincidence that a contemporary definition of lyric is "the words of a popular song" (OED), since in both poetry and music the words are illogically connected for sound not meaning.

Drama has likewise had to redefine itself so that theatricality remains its essence (Fried; see objecthood). Theater can no longer compete with special effects and personal camera angles of cinema. Instead, drama has transformed into a more presentational style, where actors more directly interact with the audience. The scripts for these plays are open-ended, and the action is customized, based on audience feedback. However, even this view of drama seems inaccurate because theatricality can be exhibited by almost anything not just actors. For example, even a piece of furniture on stage with spotlights and background music could be considered theatrical. As is, drama presents itself as an alternative to cinema or as an inexpensive way of experimenting, such as off-off-Broadway performances.

In conclusion, although the categories of narrative, lyric, and drama have been very useful in classifying and monitoring literary movements of the past, it seems like that is all they can do. Perhaps with the exception of narration, as seen in novels, movies, and TV shows, the forms fall apart when applied to modern media. After all, what exactly is the present-day equivalent of a sonnet or an ode? A radio call in show where callers discuss their mental anxieties with a quasi-psychologist! Thus, the new duty of scholars is to force modern media to work with classical models or to update old definitions.

Lirim Neziroski

Winter 2003