manuscript

Manuscript (abbreviated MS; plural MSS) is derivative of the Latin manuscriptus , from manu (ablative of manus ), "by hand," and scriptum , "written." Scribere , "to write," ultimately goes back to older forms meaning "to scratch," which distinguishes this form of writing from engraving or impressing marks into stone or clay. Thus, etymologically manuscript implies only writing with pencil or ink and some form of paper (a scroll, loose pages, a codex), though its contemporary connotation allows that a manuscript may be handwritten, typed, or electronic.

In its least restrictive sense, manuscript is written material in general, as opposed to print: that is, any written text, from papyrus scrolls and illuminated books to paper documents produced by hand. The word is also found in the phrase in manuscript , again meaning "written, not printed." [i] A second, more general, definition of manuscript --largely obsolete in contemporary usage--is "handwriting." Current English more often employs hand or script for this meaning, but the Oxford English Dictionary does cite an example of such usage from Poe's "The Purloined Letter": "He is well acquainted with my MS." In a third, slightly more restrictive sense, manuscript refers to the books and other documents of pre-print culture. Handwritten scrolls, books, and pages (journals, notebooks, historical and personal accounts, etc.), letters, illuminated manuscripts, and so on fall into this category. In short, manuscripts in this sense are works written and/or reproduced by hand. [ii]

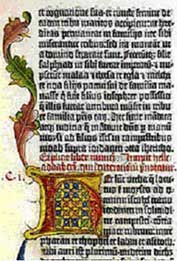

After the invention of the printing press circa 1450, manuscript began to take on a more restricted meaning. The manuscript became a text that had not (yet) been set in type --the author's original handwritten copy of his or her work, as opposed to later or final reproductions of it. Though the OED does not explicitly draw the distinction, the modern connotation carries with it the implicit expectation that this handwritten material will be published. While in pre-print culture, the manuscript was an end in itself and each was a discrete object, this later definition marks the manuscript as the starting point of print production.

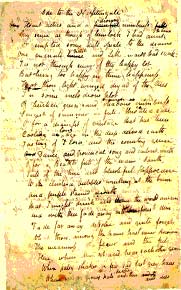

After the invention of the typewriter (which began to be mass-produced in 1874), there were at least three distinguishable stages of manuscript . Typically an author would "pen" his work, creating a messy first manuscript. Joyce's manuscripts, for example, are palimpsests of deletions and developments. From this initial manuscript, the author would usually produce a "fair copy"--written in a hand more legible to others, and containing fewer changes, marginalia, etc.--for a typist to reproduce with a typewriter. This "typescript" was then corrected, usually by hand, by the author and used in typesetting the work. [iii] From typesetting on, the manuscript was left behind, and production continued in galleys, proofs, etc. That is, once typeset the manuscript (which may have been a typescript) remained static, as it had before the invention of the typewriter.

In contemporary publishing, the identity of the manuscript has become relatively destabilized. Many authors now produce their manuscripts on a computer, which significantly alters the linearity of the writing process, causes many changes during composition to be lost from sight and from memory unless they are saved as separate files, and allows authors to send last-minute manuscript changes via email and so on. To distinguish further, in contemporary publishing manuscript usually means simply "the first copy of a work sent in by an author (either the very first version given to an editor for consideration or the first 'final draft' sent in to be prepared for publication), whether handwritten, typed, or electronic."

Electronic manuscripts show fewer signs of the process of composition than do handwritten ones. During the composition stage, the computer file is far more mutable an object than were the handwritten or typed manuscripts of yesteryear. Moreover, contemporary processes of print production are far less labor intensive. Offset printing has superannuated typesetting: now manuscript files can be reformatted into first page proofs with few errors being introduced into the text by human error. (Of course, there are all sorts of computer-generated errors with which to contend.) Suffice it to say, the current relationship between manuscript and later stages of print production is significantly different from that which existed in the past. Still, the practice of starting with a manuscript and moving through proofs to a final form remains the predominate mode of production of printed materials. [iv]

In studying written works, there is often a tension between manuscript and final product. That is, the manuscript (or even an older version of a manuscript) may shed light on new meanings or call certain interpretations of the text into question. In any case, comparing a manuscript of a work to the final version may ultimately undermine the stability and definitiveness of the final product. Two outstanding examples of how manuscript studies affect reception of a final product are Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Joyce's earlier manuscript draft, Stephen Hero , and D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterly's Lover , which was published in several editions, each with different expurgations. In each case, the authority of the published text was shaken by later comparative investigation of the manuscript. Conversely, two further examples call into question the authority of the manuscript in relation to the final product: The First Man by Albert Camus and the "Criminals" section (Book II, Part III) of The Man without Qualities by Robert Musil, as published, were never edited by their authors in proofs. Would the authors have left these books as is, approving of every word in the manuscripts they delivered to the press? Not likely. Musil, in particular, was known for making rigorous changes once he received pages from the printer.

In all print media, manuscripts are altered by the processes necessary for putting them into print. They are revised by authors, corrected by copyeditors and proofreaders, molded by editors. Indeed, in the case of authors and editors, it is difficult to say where to draw the line of "authenticity." In book publishing the author usually has the final say on creative choices while in print journalism the editor tends to have greater control. In either case, the manuscript's relation to its final version may remain in constant flux. The difference between what is considered the manuscript of a book, for example, and its published version can be quite remarkable. In some cases, a manuscript may bear little resemblance to the novel it gives rise to. Take for example Thomas Wolfe's crates of manuscript for Of Time and the River compared to the final book--one tenth the size of the manuscript--as edited by Walter Perkins.

Why do we sometimes assume the manuscript to be the reflection of the author's intent and at other times regard the final version as "set in stone"? A modern manuscript often seems to us to be the individual and relatively unmediated expression of its author. [v] Yet we always wrestle with a contradiction between regarding a manuscript as "the genuine article" (next to which certain printed versions may be corruptions) and the final work as the authority (of which the manuscript was a mere prototype). In either case, the manuscript is to be gone back to, checked against the final, when we are studying a work. The attractiveness of the modern manuscript reflects the notion of the author as the basis of literary production in a way that pre-print society had not dreamed of. Moreover, the presumed dichotomy between manuscript and printed version obscures the reality that there are many forces involved in the production of a work.

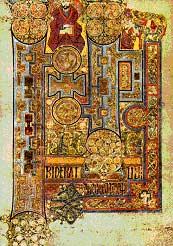

While an illuminated manuscript implies "uniqueness," the modern sense of manuscript implies more than anything else "originality." The former is the end of one type of production, the latter the beginning of another. Though the majority of pre-print manuscripts are copies of pre-existent texts, each strikes us as individual in some way. Each may be regarded as the work of one person or a group or simply as a discrete object of unknown provenance. Mass-produced books are not themselves seen as individual objects, yet their manuscripts are. [vi] The individuality of an illuminated manuscript is connected to the particulars of its presentation rather than the particulars of its content. That is, its unique use of pictures and script to mediate pre-existing material is what distinguishes this type of manuscript. In a modern manuscript, on the other hand, its unique content rather than its physical aspects is the distinguishing element. Also, a pre-print manuscript, e.g., The Book of Kells, seems to rely less on the figure of an author for its identity, while a modern one typically seems to have an intimate relation with its creator.

The modern manuscript, especially since the Romantic era, has about it what Walter Benjamin calls an "aura"--a numinous quality of "authenticity." The abovementioned Joyce manuscripts seem to reveal the workings of the author's mind, taking us as it were behind the scenes of literary creation. Perhaps because it is marked as the beginning of a process of mechanical reproduction, we perceive the modern manuscript as carrying greater ontological weight than its copies. To do so, however, requires that we simplify the process of composition and reproduction--as the account of print history above also does--and reduce the actual complications involved to a more comprehensible model based on a smooth progression of causes and effects. Within this model, the manuscript is deemed valuable, no matter whether it truly reveals something new about a published work, adds to a list of contradictions, or creates an illusion of perfect artistic creation. The manuscripts of famous works fetch a pretty penny, as though we regard them as objects comparable to the ancient manuscripts of pre-print culture.

Though manuscript always denotes a distinction between "writing" or "composition" and "print" or "final product," there is yet another difference between manuscripts of pre-print culture and those of print or post-print culture. Since "writing" and "print" coexist in print and post-print culture, "composition" and "final product" have a relation that simply did not exist before the invention of the printing press. Thus our regard of manuscripts must necessarily be different from that of pre-print writers. Indeed this difference--especially as it relates to our conceptions of the "individual"--is one of the defining aspects of modern and post-modern culture.

Brandon Hopkins

Winter 2003