kitsch

"If works of art were judged democratically--that is, according to how many people like them--kitsch would easily defeat all its competitors," observed Thomas Kulka. [1] Yet, despite its status as a source of pleasure for a mass audience, kitsch is typically considered a negative product and used as a pejorative statement. It is seen as a type of creation that reaffirms rather than challenges the collective norm, a source of sheer entertainment in opposition to the elevated perception generated by high art.

Though its etymology is ambiguous, scholars generally agree that the word "kitsch" entered the German language in the mid-nineteenth century. Often synonymous with "trash" as a descriptive term, kitsch may derive from the German word kitschen, meaning den Strassenschlamm ausammenscharren (to collect rubbish from the street) [2] The German verb verkitschen (to make cheap), is another likely source. Similarly, the Oxford English Dictionary defines kitsch in the verb form as "to render worthless," classifying kitsch objects as "characterized by worthless pretentiousness." Other potential sources also include a mispronunciation of the English word sketch, an inversion of the French word chic, or a derivation of the Russian keetcheetsya (to be haughty and puffed up).

Whatever its linguistic origin, "kitsch" first gained common usage in the jargon of Munich art dealers to designate "cheap artistic stuff" in the 1860s and 70s. [3] By the first decades of the twentieth century, the term had caught on internationally. Kitsch gained theoretical momentum in the early to mid-twentieth century, when utilized to describe both objects and a way of life brought on by the urbanization and mass-production of the industrial revolution. Thus, kitsch possessed aesthetic as well as political implications, informing debates about mass culture and the growing commercialization of society.

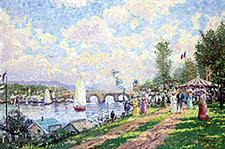

Examples of kitsch may be particular to a time and place or they may be universally applicable: Norman Rockwell's Saturday Evening Post magazine covers epitomize American World War II-era kitsch, whereas global kitsch resides in souvenir replicas of famous tourist landmarks the world over. Works of art that predate the introduction of the word into the vernacular are now deemed kitsch retrospectively: Pre-Raphaelite paintings and some Wagner compositions have been aligned with the theatrical emotionalism and affectation of kitsch. Indisputable examples of high art can be transformed into kitsch, prompting Matei Calinescu's directive that, "determin[ing] whether an object is kitsch always involves considerations of purpose and context." [4] Thus, Gustave Caillebotte's Paris Street: A Rainy Day is not kitsch, but umbrellas sold at the Art Institute of Chicago decorated with the painting's reproduction are definitive kitsch, as would be "a real Rembrandt hung in a millionaire's home elevator," according to Calinescu. (see Figure 2).

Kitsch tends to mimic the effects produced by real sensory experiences [compare simulation/simulacra , (2)], presenting highly charged imagery, language, or music that triggers an automatic, and therefore unreflective, emotional reaction. [5] Pictures of couples silhouetted against sunsets or songs with lavish, repeated crescendos elicit a conditioned response from a broad audience. Milan Kundera calls this key quality of kitsch the "second tear:" "Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see the children running in the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running in the grass! It is the second tear which makes kitsch kitsch." [6] The appeal of kitsch resides in its formula, its familiarity, and its validation of shared sensibilities. [7]

The self-congratulatory spirit of kitsch can also be seen as a deception. Kitsch holds up a "highly considerate mirror," according to Hermann Broch, that allows contemporary man to "recognize himself in the counterfeit image it throws back at him and to confess his own lies (with a delight which is to a certain extent sincere)." [8] By providing comfort, kitsch performs a denial. It glosses over harsh truths and anesthetizes genuine pain. As Harold Rosenberg perceived: "There is no counterconcept to kitsch. Its antagonist is not an idea but reality." [9] [see reality/hyperreality , (2)]

If kitsch rivals reality while simultaneously imitating its effects, then the truth of kitsch exists in its realized fabrication. Gillo Dorfles disparaged kitsch for its falsified nature: "if we have to recognize the mass-production of industrial objects originally intended for such treatment as perfectly authentic, we must regard all reproductions of unique works which were conceived as unrepeatable as the equivalent of real forgeries." [10] Whether copying a pre-existing work of art or assembling a pretense of reality, the straightforwardness of kitsch belies its inherent contradiction as a "real forgery." (see mimesis)

Kitsch's ubiquity as "the faked article that surrounds and presses in" [11] obscures--some would claim consumes--the reality that it imitates. Broch regarded the parasitic feature of kitsch as its fundamental iniquity, calling kitsch "the enemy within." He compared the difference between art and kitsch to the absolute schism between good and evil: "The Anti-Christ looks like Christ, acts and speaks like Christ, but is all the same Lucifer." [12]

Clement Greenberg emphasized that the "pre-condition for kitsch, a condition without which kitsch would be impossible, is the availability close at hand of a fully formed cultural tradition, whose discoveries, acquisitions and perfected self-consciousness kitsch can take advantage of for its own ends." [13] Kitsch does not analyze culture but repackages and stylizes it. Kitsch reinforces established conventions, appealing to mass tastes and gratifying communal experiences. "Kitsch comes to support our basic sentiments and beliefs, not to disturb or question them," according to Kulka. [14] As a result, kitsch is easy to market and effortless to consume. (see figure 2) Theodor Adorno explained: People want to have fun. A fully concentrated and conscious experience of art is possible only to those whose lives do not put such a strain on them that in their spare time they want relief from both boredom and effort simultaneously. The whole sphere of cheap commercial entertainment reflects this dual desire. It induces relaxation because it is patterned and pre-digested. [15] Class implications are not hard to recognize in analyses of kitsch. After the industrial revolution, urban working and middle classes became materially and spiritually linked to mechanized means of production, counteracting their lack of autonomy with an increased emphasis on personal leisure. The expanding distance between high art and daily life, reflected in the growing elitism of abstraction, consigned art to the province of a privileged few who, with time to cultivate their perceptual abilities, could approach avant-garde works with a trained eye or ear. For Greenberg, Adorno, and others, the growing popularity of kitsch was seen as a threat to the last vestiges of high culture in modern society.

Arguments over the relative values of kitsch and avant-garde art are linked to the ideals of high modernism and concurrent political struggles. Although the development of kitsch as a leisure pursuit may be seen as a source of relief for the lower classes, kitsch did not emancipate the working and middle classes from social inequity. Rather, as an auxiliary of mechanization itself, kitsch redoubled the dependence of the lower classes on the very system of production. Consequently, with its accessibility and broad sensibilities, kitsch could be adopted by political powers to manipulate and control the masses: "The encouragement of kitsch is merely another of the inexpensive ways in which totalitarian regimes seek to ingratiate themselves with their subjects." [16] Such discourses on mass culture can be read historically as polemics against the suppressed individuality of fascist rule.

If kitsch was a pawn, it was also a scapegoat. Beginning in the 1960s, a movement to reclaim the pleasure found in popular arts was espoused by Susan Sontag's "Notes on Camp." The camp "sensibility" offered a mode of appreciating kitsch (as well as "serious" art) because of its excessiveness, its role-playing, its overt decoration. Individuals with camp sensibilities sophisticate the understanding of kitsch, for camp judgments imply a specific way of perceiving--a trained eye or ear that stands parallel to Greenberg's elite coterie of artists and viewers.

Throughout the twentieth century, certain artists and critics have offered affirmative accounts of mass culture. European and American modernists, notably Fernand Léger and Stuart Davis, incorporated images of consumer advertisements and packaging into their paintings. Their industrialized abstract visual languages suggested a fundamental accordance between avant-garde art and mechanical production. Walter Benjamin believed that the masses could take advantage of new forms of artistic production made possible by modern technology to transform the existing power structure, using kitsch as a weapon against the self-alienation wrought by fascism. Later in the century, Pop artists seemed to embrace kitsch by using mass-production techniques to reproduce subject matter drawn from urban/suburban popular culture and commercial life. The intellectual study of mass culture was pioneered by Marshall McLuhan whose notion that "the medium is the message" annulled the supposed hierarchical distinctions between art forms. With its ability to mirror and manipulate reality, kitsch fits into McLuhan's idea of media as an extension of the human sensorium, seeming to have a life of its own but actually reflecting our own self-understanding. [17]

Whether loved or reviled, indulged or condemned, kitsch indexes mass-cultural values in a given era while simultaneously exposing the relationship between the masses and the forces controlling production. "Kitsch changes according to style, but remains always the same," [18] Greenberg declared, suggesting that, while the forms and contents of kitsch may shift over time, the nature of kitsch in relation to culture at large is invariable.

Whitney Rugg

Department of Art History

Winter 2002