artifact

An artifact (artefact in British spelling; from Latin arte, ablative of ars, art, and factum, neutral past participle of facere, to make), according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is “[i]n technical and medical use, a product or effect that is not present in the natural state (of an organism, etc.) but occurs during or as a result of investigation or is brought about by some extraneous agency.” This meaning of the term artifact has been in use since 1908, and contrasts with the first meaning: “Anything made by human art and workmanship; an artificial product. In Archćol. applied to the rude products of aboriginal workmanship as distinguished from natural remains,” which appeared in the early 19th century. In all meanings of the word, it signifies the presence of an artificial object or element, in contrast with a natural medium.

The word artifact has come into popular use mainly due to wide developments in imaging technologies, starting with the telescope, but especially since the invention of photography, and most recently with the proliferation of digital technologies. Although the applications of such technologies were at first primarily technical and scientific, they quickly became parts of people’s daily lives (the telescope has always been a curiosity for the public, and digital photography has recently become a regular practice for most households). Therefore the current definitions of the word, not totally acknowledged by the Oxford English Dictionary, depend heavily on context, and the contexts in turn depend on technologies with which the artifact is associated.

This article looks into this blurry modern meaning of the word, that of an element observed in a system that isn’t a part of its natural state. Wiktionary defines artifact as “A structure or feature, visible only as a result of external action or experimental error.” [2] Indeed, the technologies which produce signals accompanied by artifacts are many. I will illustrate those artifacts that are most often encountered in popular uses of imaging technologies: chromatic aberrations, film grain enlargement, digital image capture artifacts. Many others could be mentioned, such as digital compression artifact and sonic artifact.

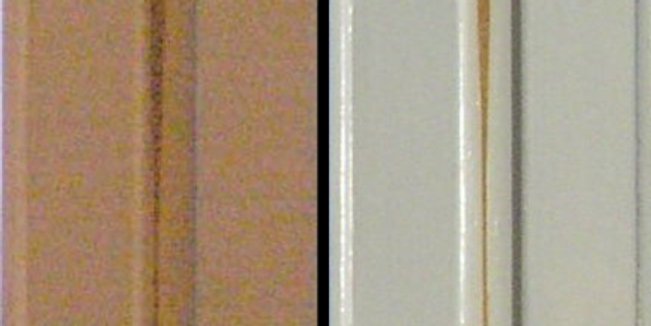

Chromatic aberrations are noticeable in the form of “fringes” of color around edges in images obtained through any equipment that uses a lens to focus light (i.e. telescope, microscope, camera).

[3]

An example can be seen in picture (B). Chromatic aberration is “caused by a lens having a different refractive index for different wavelengths of light”, which causes different wavelengths of light to have differing focal lengths. Though perfect correction cannot physically be achieved (our eyes are susceptible to minimal chromatic aberration as well), the artifact can be minimized through the use of an achromatic doublet, the binding of two materials with differing dispersion to form a single lens. Picture (A) in the above image was taken using such a lens, which is common today.

Film grain is a well-known analog artifact. We see it when we go to the movies, where a typically 16mm or 35mm gauge film is lit in a projector, and its image enlarged to fill a screen that is enormous compared to itself. The grain of the film is visible as the analog picture element, the unit of chromatic information, especially in the case of 16mm film, where more enlargement occurs to fill the same sized screen. Film grain is also visible on some photographs, which are enlarged images from a film source. Even when invisible to the human eye, (i.e. on small enlargements or contact prints, in the case of photographs) the film grain still influences the appearance of photographic images, which is noticeably different from human vision. In both photographic and film images, hairs, dust, scratches, and other physical imperfections on the film are also often visible.

In digital cameras, the image sensor is the CCD, charge-coupled device, or the CMOS, complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor; the storage medium is a digital storage device, onto which binary information is stored, and later reconstructed to form the image on a display device or output in physical form through a printer. Both the sensing and storing processes are digital, a fundamental difference compared to analog technology. The picture element, instead of the film grain, is the square pixel, which is responsible for the inherently sharper look of digital photographs.

[4]

Because of the grid-like arrangement of the square pixels, digital photographs are susceptible to Moiré patterns.

[5]

This happens when a grid pattern in an object happens to be at a similar frequency to the pixel grid of the image sensor, and the two are at a slight angle. The more random arrangement of particles in the film grain prevents Moiré patterns from occurring. A higher sensing resolution (more pixels), in other words a higher spatial frequency of pixels than lines in the pattern of the object being captured will prevent Moiré patterns from occurring in digital photographs.

Because of the poorer dynamic range of most image sensors compared to film, over- and under-exposures tend to occur more often in digital photographs.

[6]

Too much light saturates the sensor and are displayed as white pixels (with no value or chroma), whereas too little light fails to activate the sensor, and are displayed as black pixels.

More obvious are digital noise and “blooming”. Digital noise occurs on lesser grade sensors, when the background electrical noise generated by the sensor itself is picked up, and is displayed in darker areas of the image where no other information is captured.

[7]

Blooming occurs when a sensing unit is saturated with light, and the electrical charge it produces “overflows”, influences neighboring pixels, so information is lost overall.

[8]

Finally, if the image is stretched to fit a display, in much the same way as an analog image is enlarged by a projector, such that the picture elements are visible, the digital image will appear as made of square pixels, so that diagonal lines or edges appear “jagged”, and the image falls apart dramatically. This is called aliasing.

[9]

All of the above artifacts come in the way of our perception of (in this case) the photographic image. They create an artificial distance between us and the view of the world offered by the lens. The resemblance of this view to that of our naked eye is such, especially compared to the older media of painting and sculpture, that any artificiality has come to appear as an annoyance, an error, something that “isn’t supposed to be there”, something external to the system of the image. The material reality of artifacts has become unacceptable, now that photography and the digital media are imagined to be transparent, and more independent of their material support than ever before.

In fact, in the two models of “vernacular reflections on media” according to W.J.T. Mitchell [10], the digital and photographic media are oftentimes thought according to the communication model, as media “through which messages are transmitted”, rather than the art model of media “in which forms and images appear”. The term artifact in its modern use seems to be exclusive to the communication model, which tends to maximize signal over noise, maintain output in relation to input, and erase the materiality of the medium for the sake of the efficiency of communication. In science artifacts are undesirable because they come in the way of the scientist’s observation of nature. In the art model, artifact, artificiality, or noise, so to speak, would be essential, since the concern is aesthetics, the how, and not the what.

In either model, a system of representation is established, relative to which artifacts are considered external. Whereas the art model embraces this outside environment, recognizes it as a breeding ground, a medium for forms to appear (like bacteria are cultivated in a medium), the communication model chooses to dismiss all that is outside the system as irrelevant. Before the era of cable television, one would watch a screen full of noise resulting from less than perfect signal, and yet one blocks out such an artifact to focus on the information contained in the program; one ignores the color dot matrix that make up the images of large billboards, until they are far enough from it to see the complete image. In the communications model, one ignores artifacts in much the same way as one’s consciousness delegates the repetitive action of pedaling a bike to one’s motor memory, in order to focus on steering and controlling speed.

In this respect, an artifact is unnecessary, unwanted, in essence a supplement, a concept which Jacques Derrida has remarked is paradoxical, because it implies both a completeness and an incompleteness to a system: the system should be self-sufficient, and yet if it were, it would not need the supplement. [11] Derrida states that the supplement demonstrates the existence of an “originary lack” in the system, which the supplement corrects for. Thus what seems at first to be an “inessential extra” worn on the outside of an apparently complete system can turn out to be a vital part of its interior, filling an essential void in it.

This concept complicates the systems theory of Niklas Luhmann, [12] which delineates an inside and an outside to a system. The deconstructionist theory of Derrida suggests that the artifact, if it can be seen as a supplement, could be on either the inside or the outside of the system, depending on one’s point of view.

My article can end here, but I’d like to offer some further reflection on the place and role of the artifact through the media of theater and film. Both have a rather dense concentration of artifacts; for theater: blocking (where actors stand), costumes, make-up, lighting, set, etc.; for film: in addition to all that, cinematography, montage, and the many physical artifacts related to the camera, the film, and the projection, as detailed earlier in this article. We typically approach theater with the art model of the medium: we embrace the artifice, we do not genuinely take the performers as their portrayed characters: we simply play along, “the theater of artifice”.

However, our approach to film is twofold: while we as scholars analyze it as an art, according to the art model (Bamboozled is an open invitation to do so, because of its obvious embedding of a variety of media within itself), we can rarely afford to be critical of the medium while we watch the films. The experience of a movie-goer, whether in an academic context or not, is at least partially dictated by the communication model, in the sense that the artifacts of film grain (or in the case of Bamboozled, digital artifacts as well), montage, over- and under-exposures, etc. are being ignored, in order to allow the narrative to unfold.

In fact, our approach to theater is twofold as well: especially in the case of a new play, we suspend our disbelief in regular intervals, in order to understand the story. One can say of the artifact, if it can be applied so liberally as to describe elements of artifice in art, that it is inherent in all media, and that when apparent to the spectator or receiver, it raises their consciousness of the medium itself.

Yi Zhao

Winter 2007